Biological reactions

Our brain is programmed to manage on its own the procedures relating to the functioning of our anatomy. Our digestive system, for example, does not need us to think about how our stomach, liver or intestines work to do its job.

Our brain also manages emergency situations: when we are in danger, a complex process immediately takes place to give the body enough resources to fight or flee for survival.

|

|

|

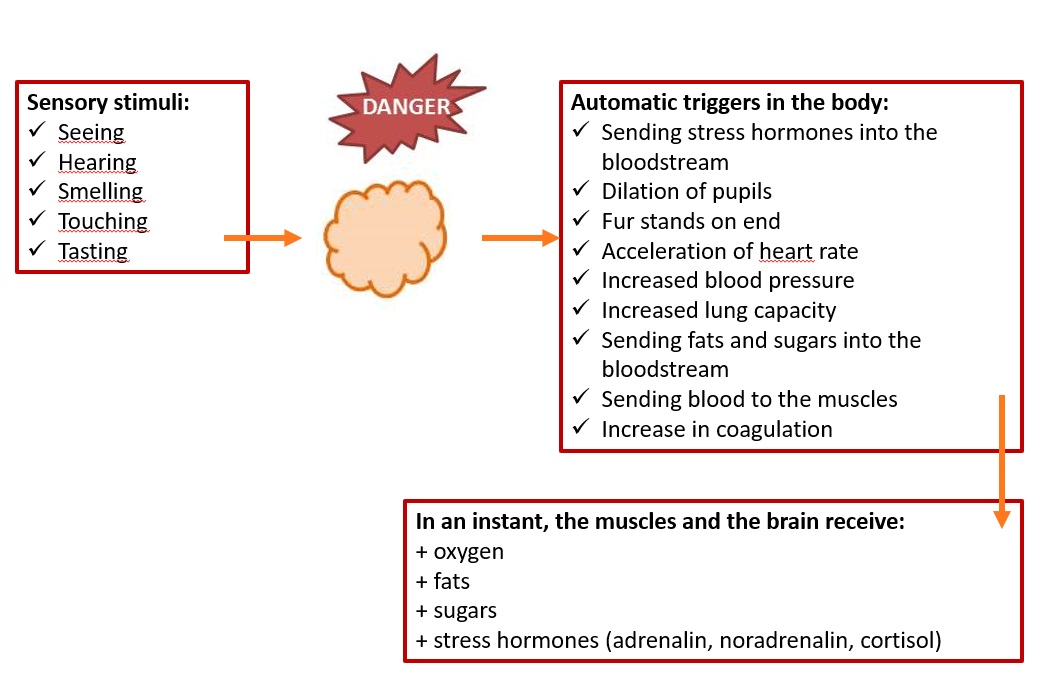

Let’s consider an example: during a walk, suddenly a loud bang is heard. Instantly, our brain prepares our body for danger by sending oxygen, fat, sugar and stress hormones into the body. The blood leads all these elements to the muscles so that we can run away or fight. See process A below.

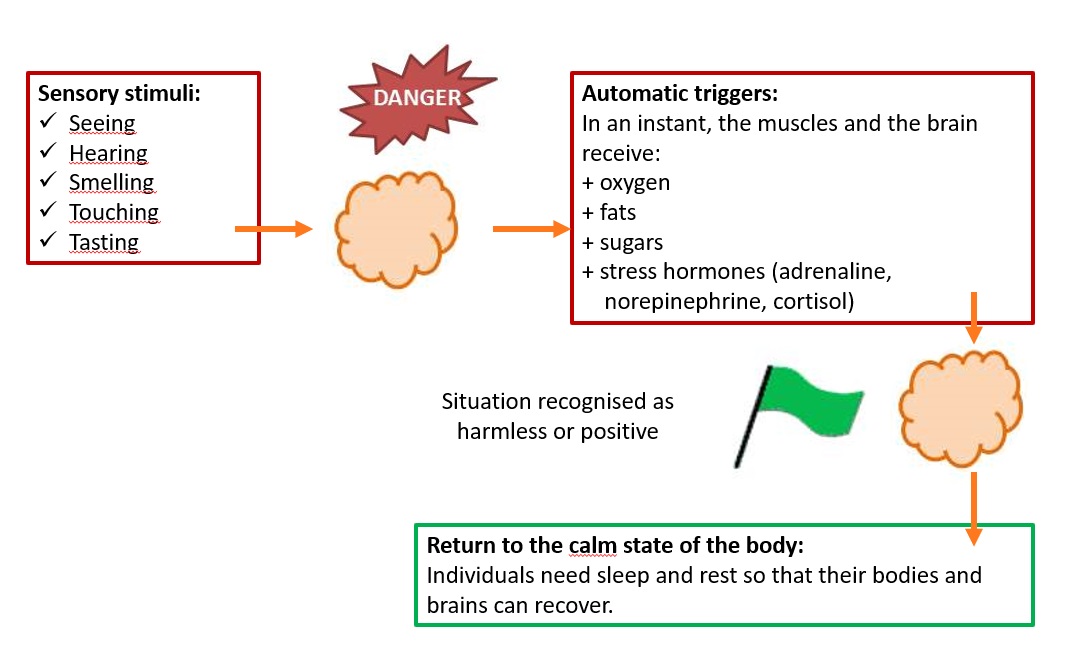

Let’s say that it was not a dangerous situation, but perhaps just some joker who popped a balloon. The danger is averted: the new stimuli reach our brain, which sends the necessary messages to the different organs to return to a calm situation. Does our body instantly return to the same state it was in before the bang? Certainly not. A state of tiredness and hunger is often felt as a result of the fats and sugar used. It will also take time for the effects of the stress hormones to be eliminated (adrenalin: 1 to 6 days / cortisol: much longer). See process B below.

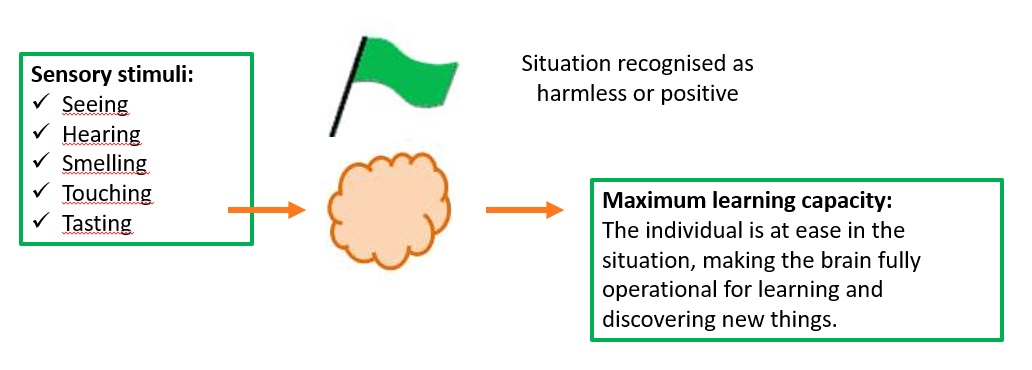

Let’s now assume that we regularly take part in hunting parties. We are familiar with the sound of gunshots and have incorporated them as part of an activity that we enjoy. This means that the brain does not trigger the alarm procedures, and we can enjoy our activity in a relaxed manner. See process C below.

A. Automatic process when somebody feels unsafe

The body is prepared for fight or flight

B. Automatic process when somebody learns to cope the situation

The body goes through a state of alert, to return to calm

C. When the individual copes the situation

The body remains in a normal state of calm

These processes are identical in our dogs: their brains are programmed to react in case of danger.

A stressful situation generates stress hormones every time it occurs. If an individual is sensitive to a certain stimulus or situation that occurs frequently, the hormones are released every time. Anatomy has not yet been able to completely eliminate the old effects of hormones, so new effects accumulate.

Just like stress, an exciting activity produces the same effects on the body. If a dog is hunting, his body will use all available resources (oxygen, sugars, fats and stress hormones). To catch its prey, it will need both speed and endurance. If these hunting parties occur frequently, our dog’s body will be overloaded with adrenaline, noradrenaline and cortisol.

When we throw a ball, stick or frisbee for our dog, we repeatedly reproduce this hunting scenario, and thus initiate this biological mechanism of stress hormone production.

If these exciting and/or stressful situations occur frequently, our dog’s body will find itself in a situation of chronic stress, with all the possible pathologies that may result (hypersensitivity to visual and sound stimuli, difficulty concentrating, loss of appetite and digestive disorders, sleep disorders, irritability,…).

Biochemical reactions

When the body produces adrenaline, there is a parallel production of other substances which are not without consequences.

- Gastric fluids: these can lead to diarrhoea or loose stools, vomiting, digestive problems;

- Anti-diuretic hormones: they cause an increase in urine production (our dog will pee much more often);

- Neuro-hormones neuropeptides Y: they damage the immune system;

- Sex hormones: they cause changes in behaviour, such as humping or increased irritability.

Any stressful situation causes changes in the body, small or big, depending on the intensity of the stress and its duration. In the case of recurring stress, we speak of chronic stress.

Chronic stress is harmful to health (digestive problems, allergies and skin problems, body and mouth odour, high heartbeat, high blood pressure, drinking a lot, …) and leads to behavioural problems (excessive barking and howling, nervousness and irritability, depression and lack of social skills, pulling on the leash, …).

The uniqueness of each individual

The ideal for optimal learning is to avoid exciting and/or stressful situations. In the case of too much excitement or stress, the brain is monopolised by physical survival reactions and therefore cannot handle anything else in the same period of time. New information is not acted upon because the brain is unable to deal with it.

It is important that activities respect the physical, emotional and learning capacities of each individual. Like any other species, dogs are not all made in the same mould. The origin of the breed can be important, but within a breed, a lineage, a kennel, even a litter, each individual is born with particular abilities (physical and mental). And as with humans, every day is not the same, and every individual has variables: every individual has weak points and off days. It is the same for our dogs.

Let’s take a visual stimulus: the passing by of a bicycle. Some breeds are indeed predisposed to chase anything that moves quickly. This does not mean that all individuals of that breed will react in the same way to the same stimulus. Logically, the reverse is also true: not all individuals of a placid breed will necessarily remain unresponsive to the same stimulus. Individuals of the same breed have things in common, but each individual remains unique.

Depending on one’s experience, these differences are even more obvious. A dog of a breed known to be placid, who has had a negative experience with a bicycle (fear or physical injury) will become reactive (or not…) to the passing by of any other bicycle.

Every day is also different: if our dog is feverish (not enough rest? accumulated fatigue? sick or injured?), he will be less tolerant on that particular day than on any other day of the year.